The following article, recently published in The Australian, was well received by a cross-section of Australian society. However, it received a minor backlash from proponents of a gendered viewpoint who restrict their violence awareness campaigns to male against female violence. We applaud Dr. Ahmed’s gender-inclusive approach to discussing family violence, along with his permission to republish the article at Whiteribbon.org

_________________

THERE is too little acknowledgement of the importance of male disempowerment in debates surrounding domestic violence. Gender relations have changed dramatically in the past few decades, but discussions about family violence are stuck in the mindset of 1970s radical feminism.

This emphasises power inequality in gender interactions and on perceived societal messages that sanction a male’s use of violence and aggression. The focus is on male villainy, denial of biologically based sex differences and a cult of victimhood. This is part of a broader movement that defines normal maleness as a risible kind of fatuous and reactionary behaviour. As US anthropologist and masculinity expert Lionel Tiger, who coined the term “male bonding”, says: “We have a psycho-prejudice, in which the norm is the female norm and what boys (and men) do is seen as socially disruptive.”1

The Prime Minister’s move to acknowledge the Australian of the Year award to Rosie Batty and community outpouring on domestic violence through a COAG committee is worthy, but it risks becoming dominated by radical feminists and a worldview around the powerlessness of women.

Just as women are now more likely than ever to enter university, be breadwinners and have affairs, they are also more likely to commit family violence against partners, children or relatives. But the anti-feminists who focus on female perpetrators of family violence, such as Michael Woods from male advocacy group Men’s Health Australia, forget the growing social and economic disempowerment of men is increasingly the driver of family based violence. Woods is a strong critic of what he says is a domestic violence industry and diluted measures of what constitutes violence.2

The focus on female disempowerment alone will not achieve an improved existence, since they are often surrounded by disempowered men. Men for whom the security of unionised labour in the manufacturing industries is becoming a distant memory are experiencing a huge displacement from modern economic trends. It’s been replaced by casualised, service-oriented work with relatively low wages. In essence, their work has been feminised.

The focus on female disempowerment alone will not achieve an improved existence, since they are often surrounded by disempowered men. Men for whom the security of unionised labour in the manufacturing industries is becoming a distant memory are experiencing a huge displacement from modern economic trends. It’s been replaced by casualised, service-oriented work with relatively low wages. In essence, their work has been feminised.

British social researcher Paul Thomas questioned British youths of different backgrounds for a study in 2010. He found white, working-class men feel they are the real outsiders and disenfranchised from opportunity.3

Likewise, family violence within newly arrived ethnic groups is often related to the sudden dilution of traditional masculinity, leaving men lost and isolated, particularly as females enjoy greater autonomy and expectations. This is primarily positive, but a greater acknowledgment of the huge displacement such men endure from the cleavage of the institutions of family, clan and tradition in less than a generation may help alleviate their sense of humiliation.

Despite the cries of domestic violence being an epidemic, we should also consider that fatherlessness could fit such a category, with 40 per cent of Australian teenagers living without their biological fathers. It was Margaret Mead who said fatherhood was essentially a social invention. But as the Left increasingly dilutes the notion of biological differences in sex, amusingly illustrated by Greens senator Larissa Waters imploring parents not to buy gender-specific toys for Christmas, we are downplaying the notion that fathers are even desirable.

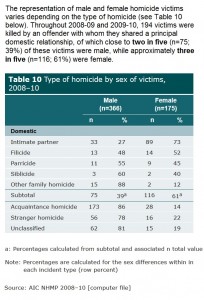

Statistics don’t lie. It is true one woman a week dies at the hands of a partner, current or former. As part of a broadbased strategy, it is critical that improving arrest and prosecution rates, establishing shelters and abuse hotlines, pushing for state provisions against stalking, and creating protections for immigrants all have the goal of getting victims out of abusive relationships.4

But the broader movement that has long fought against violence towards women remains stuck in a view of gender relations from decades past, which will limit its effectiveness in stemming the problem in an inclusive way.

Sources:

[1] Lionel Tiger, Who Needs Men?, Harper’s Magazine, June 1, 1999.

[2] Micheal Woods, The Rhetoric And Reality Of Men And Violence, NMHC, Adelaide 2007.

[3] Paul Thomas, Responding to the Threat of Violent Extremism, Bloomsbury Academic 2012.

[4] Marcot, A. Stopping Domestic Violence: A Radical Feminist Idea? The American Prospect, 2013.

| About Dr. Tanveer Ahmed

Dr. Ahmed has experience in entertainment, journalism and politics, and is a regular media commentator appearing across Channel 7 on Sunday Night, Daily Edition and The Morning Show. He has also appeared on ABC’s Q&A, 7:30 Report and Lateline. He has previously been a columnist for the Sydney Morning Herald focusing on mental health and social issues. He is a published author and his memoir of migration and medical training is called “The Exotic Rissole”. Website: tanveerahmed.com |